Fentanyl Increasingly Dangerous to First Responders

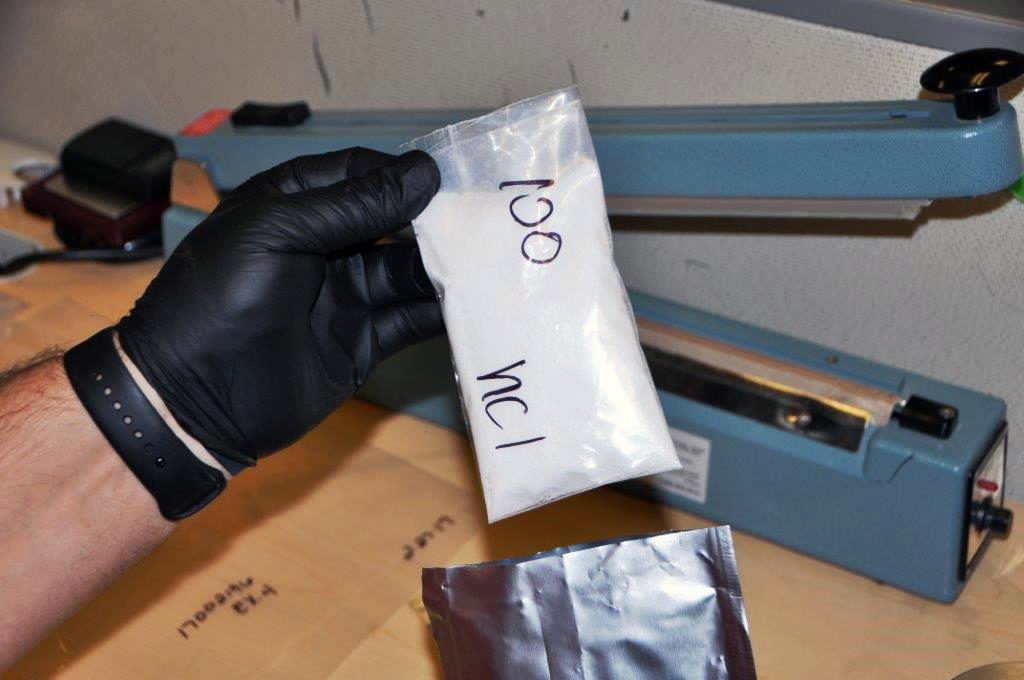

The explosion of the opioid epidemic that is responsible for thousands of overdoses and deaths is a consistent problem that EMS and law enforcement encounter on an almost daily basis. Usually, the victims of these powerful drugs, such as heroin and fentanyl, are opioid users, who EMS personnel and law enforcement are regularly called to assist. However, first responders are also being warned about the increased risks they face of being exposed to these deadly drugs, specifically fentanyl—a popular synthetic opioid that is 40 to 50 times more powerful than heroin. To respond to these dangers, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) released a field guide called “Fentanyl: A Brief Guide for First Responders” for EMS and police who find themselves responding to opioid-related calls.

“We need everybody in the United States to understand how dangerous this is,” Acting DEA Administrator Chuck Rosenberg warned. “Exposure to an amount equivalent to a few grains of sand can kill you.”

The warnings have become more urgent in recent months due to numerous cases of accidental overdoses and exposures involving EMS and police.

In May, Chris Green, a police officer with the East Liverpool Police Department, was accidentally exposed to fentanyl during a routine traffic stop after he inadvertently ingested the drug through his skin. Green needed four shots of Narcan, an emergency overdose medication, to be revived after collapsing from the effects of the drug. In another case, two Paramedics and a sheriff’s deputy in Hardford County, Maryland, were treated after showing signs of opioid exposure while treating an overdose victim.

“It is important to get the word out to everyone because it may be the first responder who needs to have Narcan administered,” said Baltimore City Health Commissioner Leana Wen.

The risks of accidental exposure are so high, in fact, that some emergency personnel have even begun carrying Narcan kits for drug-sniffing K-9s, just in case the dogs ingest the deadly drugs.

The DEA guide, along with a National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health manual on preventing fentanyl exposure, suggests certain precautions be taken to lower the risk of coming in direct contact with the substance. Personnel should be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of an overdose, be aware of the ways fentanyl can be ingested, and only allow trained professionals to handle substances that are suspect.

“Assume the worst,” Rosenberg said. “Don’t touch this stuff or the wrappings that it comes in without the proper personal protective equipment.”

The DEA video “Fentanyl: A Real Threat to Law Enforcement” offers advice on how police and EMS can protect themselves from the dangers of fentanyl.

Cross-Cultural Communication for EMS

Ambulance services interact with people from all walks of life, and from all parts of the world. AAA checked in with expert Marcia Carteret, M.Ed., for some tips for communicating more effectively with people from other cultures. Marcia is an instructor of intercultural communications at University of Colorado School of Medicine in the Department of Pediatrics. She trains residents, faculty, and staff in healthcare communication with a focus on cross-cultural patient care and low health literacy. She has also trained in over 120 private pediatric and family practices across Colorado.

Marcia also developed a robust cross-cultural toolkit for AAA members. [Learn more about AAA membership]

Barriers to Understanding

In all healthcare settings, successful communication with patients and families depends on awareness of three key barriers to their understanding and compliance:

- Cultural Barriers: Understanding western medicine and the U.S. healthcare system is a challenge for many of us, but it is especially problematic for recent immigrants and refugees. 72% of U. S. population growth in the next 20 years will come from immigrants, or the children of immigrants.

- Limited English Proficiency: The number of people who spoke a language other than English at home grew by 38 percent in the 1980s and by 47 percent in the 1990s. While the population aged 5 and over grew by one-fourth from 1980 to 2000, the number who spoke a language other than English at home more than doubled.

- Low Health Literacy: While poor understanding of the health care system and difficulty understanding health care instructions may be associated with language and cultural barriers, low health literacy is also found in patients who are proficient in English and who share the common U.S. culture. This latter group may be especially at risk of having their low health literacy go unrecognized. 90 million “mainstream” Americans cannot understand basic health information.

Addressing These Barriers

How do people understand one another when they do not share a common cultural experience? Nowhere is this a more pressing question than in healthcare settings, especially in emergencies. There is no easy list of things “to do” or “not to do” that can be applied to each culture. What can be useful are communication guidelines that work for people from all cultures. These guidelines are also important for people with low health literacy.

[quote_left]“The essence of cross-cultural communication has more to do with releasing responses than sending messages. And it is most important to release the right responses.” — Edward T. Hall[/quote_left]

Perhaps the most important is framing questions to elicit appropriate answers. As Edward T. Hall, anthropologist and cross-cultural researcher wrote,“The essence of cross-cultural communication has more to do with releasing responses than sending messages. And it is most important to release the right responses.” What could be more crucial when, for example, an EMT or paramedic is attempting to establish level of consciousness by directly eliciting information from a patient? Being able to get quality responses from patients from any culture is a communication skill that comes with experience. Learning and practicing a set of strategically designed questions is key to building confidence in this important skill.

Key Communication Tips

- Explain your professional role

911 is the number to dial in an emergency, but some people may not understand the roles of different emergency responders. You can’t expect people who are still learning to function in the U.S. mainstream society – recent immigrants or refugees especially – to understand the role of the EMT or paramedic.

Suggested explanation: “I am not a doctor. I am an emergency medical professional. I have come to help because someone called 911. I will take this person who is hurt/sick to the hospital safely.”

- Use simple familiar words and short sentences

“Stabilize” is a complex word, even though it might be the best word to describe what you do for a patient in an emergency. Help is a better word. With Limited English Proficiency (LEP) patients and families, the 5¢ word is always better than the 75¢ word. Basics such as give, take, more, less will be better choices than administer, increase, decrease.

- Be clear when you are asking a question versus giving an instruction.

Running questions and statements together is confusing for second language learners. Avoid sentences like this: “It looks like you are having a reaction (a statement of observation) so I need to know if you have taken any medication that made you feel sick.”Examples of concise phrasing:- “What medicine have you taken?

- “Show me this medicine.”

- “Show me where it hurts.”

- Avoid close-ended questions

These usually begin with do, did, does, is, are, will, or can. These can be answered with a simple yes or no – or a head nod. Avoid the use of close-ended questions with Limited English Proficiency (LEP) patients because in many cultures people will frequently simply say yes even if they don’t understand you. - Use open-ended questions

These usually begin with the 5 Ws – who, what, when, where, why (and how or how many). It is awkward to answer these questions with a nod, shrug, or simple yes/no. For example, you might ask: “When did you take these pills?” instead of “Did you take these pills?” - Avoid starting sentences with negations such as isn’t and didn’t.

Though this is a common speech pattern in English, it may be confusing for people who speak a different native tongue. For example: Didn’t you call 911? (Read more about this speech pattern.) - Clarify understanding – yours and theirs

Even if you are using simpler words and shorter sentences, you can’t be certain there has been communication until the receiver acknowledges it with feedback. Remember, head nodding does not count as feedback with people from many different cultures. Even with Americans, and definitely with children, head nodding is often a sign of partial comprehension. So you must ask clarifying questions. - Repeat back what you have understood.

- Examples: “Yes? – you took the medicine?”

- “Yes? – you are his/her grandmother?”

- Not understanding vs. misunderstanding

When people do not understand what you say, there is more likely to be an indication of confusion than when they MISunderstand you. A person struggling with English, for example, may ask you to repeat what you have said. Their face may show confusion. But when people MISunderstand, it can be far less obvious. For example, the English words want and won’t sound very much alike to a non-native speaker. You may say to a person, “I want to help you,” but she may hear “I won’t help you.” She may be perplexed that this is your response, but she may be very inclined to accept the word of a healthcare professional. She may perceive you as being uncaring, but certainly won’t say so. Many MISunderstandings go unnoticed by both parties. Asking clarifying questions is crucial. - Speak slowly and clearly—NOT loudly

Often when people don’t understand our language, we treat them as if they are hearing impaired or “slow” without realizing we are doing so. Articulate your words in shorter phrases rather than just speaking more loudly.

Cultural Norms

Cultural norms vary around the world. Here are some key norms to keep in mind when assisting patients and their families.

- Eye Contact

An EMT or Paramedic will often be perceived as an authority figure by the people from more traditional cultures. If a person is avoiding eye contact while listening to you or while answering questions, be aware that in some cultures direct eye contact with an authority figure is very rude. In trying to be respectful, people may appear to be avoiding looking you in the eye. This is not to be taken immediately as any indication of disrespect, dishonesty, or evasiveness - Silence

Silence may be the only response a person can muster if he or she is frightened. Silence might also be a way of showing respect, similar to avoiding eye contact. Being thoughtful about answering a question shows humility and real effort in giving the best answer. Unfortunately, silence on the part of the non-English patient or family member is often interpreted as open hostility by Americans. It can be helpful to say: “I need your help. Please try to answer my questions. Your answers help me help you.” Also, try not to rush answers. Americans allow very little time between questions and responses. Impatient and in a hurry we tend to start talking before the other person is able to answer the question asked. - Reverting to Native Language

Bilingual patients may revert to their language of origin in times of stress, and while this hinders communication with an EMT, it should not be seen as manipulative or uncooperative. Calmly ask the person, “Can you speak in English? Please try English.” If the person does not speak any English, this will at least help them realize you can’t understand.

Summary

As first-responders, EMS is often working in high stakes situations where communication is a challenge even without the added barriers associated with the “triple threat” to healthcare communication—language barriers, cultural understanding, and low health literacy. No matter which culture an EMT or Paramedic is interacting with, the key to good communication is asking good questions and phrasing all dialogue in simple short sentences. It should be clear that a question is being asked or a statement of information is being made by the EMS professional. Asking for clarification is essential. Head nods and affirmative answers should not be accepted immediately as evidence of sufficient understanding or agreement. EMTs will find that enhanced communication skills will not only improve cross-cultural interactions, these skills improve outcomes with all people – even “mainstream” Americans. Also, be aware that low health literacy is a problem for 90 million Americans. Never assume that same-culture communication in English requires less intentional speech on your part.